The Phule We Remember: As remembered by Mahadu Sahadu Waghole

[Beginning September 24, The Satyashodhak has been publishing the translation of the Marathi book Amhi Pahilele Phule (ed. Sitaram Raikar, Mahatma Jotirao Phule Samata Pratishthan, 1981) serially. This collective translation is an initiative of the Abrahminical Histories of a City Collective, Pune.]

My name is Mahadu Sahadu Waghole and I am 75 years old. I was 25 when Jotiba passed away. I am the eldest son of his niece Thakubai. When my grandfather moved to Pune, we lived in a house that was owned by Jotiba. We were neighbours. I remember many details about him. In a society where widow remarriage was not permitted, he started an orphanage for widows so they would not resort to abortion in cases when they had taken the wrong path. By the time I was old enough to understand, many women had [already] given birth and left their children at the orphanage. I remember a few deliveries very clearly from the time when I first began to understand such things. There were 30-40 children in that ashram. Many of them died during infancy, while some survived up to the age of eight to ten. There were three or four children who lived for about eight to ten years. Their names were Shantaram, Baburao, Laxmibai and Yashvantrao. Among these, only Yashvantrao survived.

Jotirao had printed advertisements in big type, akin to theater-play posters, to stick on the city walls. I was in possession of a few of those posters for a while. The advertisements were titled ‘kāḷe pāṇī ṭāḷṇyācā upāy’ (a way to avoid being sent across the seas), stating that women who were pregnant out of wedlock could go to Jotirao Govindrao Phule’s house to deliver their child. The advertisements also stated that the woman’s identity would be kept confidential. He stuck these bills across the city of Pune and also arranged for their display in pilgrimage towns like Pandharpur, Nashik, Wai and Kashi. The expenses for this orphanage were funded from his own pocket.

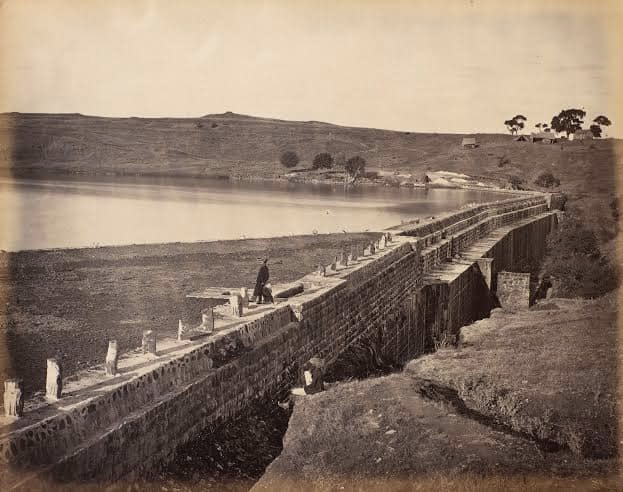

Everyone would address Jotirao as Tatya. As a contractor, Tatya had undertaken many big construction projects. It was him who built the Katraj Tunnel. That work must have been completed when I was very young because I heard about it from him and others when I became older. I saw him supply lime, stone and rubble for the Khadakwasla Dam. Similarly, he had received a contract for supplying lime, stone etc., for the Yerwada bridge and for many other construction works. He was also the contractor on the project to build pipelines on the Mula-Mutha Dam. He earned thousands of rupees as profit in this trade.

Secondly, Tatyasaheb was a very good friend of Vasudeo Babaji Navrange from Mumbai. Vasudeo Babaji had gone abroad and managed to acquire the principal agency in India for metal casts from an English company, and, from him, Tatya had acquired the sole agency for the Pune division. Industrialists would buy these casts for pouring metals like brass, copper, silver and gold. Tatya was the only one who had a metal casts shop in Pune and therefore he earned a significant income in this trade — about a hundred rupees daily. The shop was located in Vetal Peth and two people were employed to look after it. He owned land in Khanwadi, which he had given to the poorer branch of his family for their sustenance. He did not take any share of the income from this land.

Earlier, he had set up schools for Mahars and Mangs. From the students who studied in those schools, Dhondiba Bin Lahuji, Vetal Chambhar etc., created a lot of awareness among the Mahar-Mangs in those days. Under Jotiba’s supervision Dhondiba taught children chaḍīpaṭṭā (a flexible, belt-like sword) in the wrestling talim (arena). Tatya had learnt dandpatta, wrestling, archery and so on in Lahuji Bua’s talim. I used to go to Dhondiba’s talim.

As a schoolgoing child, I would sometimes skip school and run off to Tatya’s farm in Manjari. On a couple of such occasions, Tatya spotted me and not only gave me a sound thrashing but also lectured me about the importance of education. My father Sahaduba Waghole was employed as a supervisor in Tatya’s farm. Tatya strove for the education of children from backward backgrounds, often helping poor students with fees and books. He was perpetually preoccupied with his pursuit of spreading education. In public meetings he raised the demands for compulsory primary education in our country, and for the government to enact a law along the lines. He asserted that the lack of education had led to the ruin of our country and the sinking of our artisans and farmers, and therefore, for the country’s progress, education should become a public good. He worked towards this goal his entire life.

He went from village to village to spread his ideas and thoughts. I also accompanied him at times. His travels often took him to the areas of Saswad, Junnar, Ottur, Solapur, Satara, Mumbai, Konkan and Baroda. Once, on the invitation of the King of Baroda, Shrimant Sayajirao Gaekwad, he stayed in Baroda for three months. He had taken my father Sahaduba Waghole with him for his arrangements, who later told us how Jotirao stayed in Baroda as a guest of the Maharaj. He would dine next to the king. Tatya and Maharaj would regularly engage in conversations and Maharaj would heed Tatya’s counsel. Maharaj would talk to Tatya everyday for an hour. Maharaj heard all the four parts of Tatyasaheb’s Shetkaryacha Asud, and he respected Tatya a lot. And similarly, Shrimant Sayajirao Maharaj would visit Pune once a year, and whenever there, he would invite Tatya to meet him. Tatya and Maharaj shared a close and cordial relationship. When Tatya fell ill, Maharaj sent money for medicines and daily expenses.

Even though Tatya earned lakhs of rupees in trade and business, he spent all that money for the upliftment of his people and for helping the poor and the downtrodden. Towards the end of his life, he had fallen into acute poverty. He was left with nothing but his house. After his death, his wife Savitribai, and son Yashvant had to contend with immense difficulties. They had money neither to run the house, nor for Yashvant’s education. Tatya’s friends conveyed these circumstances to Shrimant Sayajirao Gaekwad, who sent some money to Savitribai. With that amount, she frugally managed the household and Yashvant’s education.

In 1884, with the aid of Shete of Junnar and Bhau Kondaji Patil of Ottur, Tatya organised a gathering in Junnar. Tatya had organised many such meetings in the Junnar area to spread the message of the Satyashodhak Samaj, and had also opened many schools in the region. Bhau Kondaji Patil, Jotirao’s elder cousin, was a fierce and influential personality. He contributed significantly to the work of Satyashodhak Samaj in that region. He had great respect for Jotirao. As a result of Tatya’s Satyashodhak movement, farmers in the Junnar and Konkan regions had launched satyagrahas against the moneylenders and the priestly class. The tenants had refused to cultivate their masters’ land and left the farms untilled as a response to the extravagant rents. He also gave many lectures in Mumbai. Prominent personalities like Jaya Karadi Lingu, Sayaji Molhuji Contractor, Raghu Balaji, Venku Baluji, Narayan Meghaji Lokhande, Ramayya Venkayya Ayyavaru etc., would help him [in Mumbai].

Yashvant, who came from the orphanage started by Jotirao, turned out to be quite saintly. He took good care of Jotirao, and then of Savitribai after Jotirao’s death. He was an affable, calm and thoughtful boy. After Tatya’s death, he became a doctor. He landed a high post in the military; as a doctor, he was posted to China and Kabul. After returning to India, he resided in the Ahmednagar Cantonment. During the first wave of the plague in Pune, Savitribai passed away. Yashvant returned to Pune on hearing the news of her sickness, and on his return to Ahmednagar, he died of the plague. There is no doubt that Yashvant was well-mannered and a gentleman. Yashvant’s mother was a sister of a Brahmin mamlatdar (revenue officer); she was from the Kalyan-Bhiwandi area. When she was widowed, she got pregnant due to licentious behaviour and was sent to Tatya’s orphanage by the mamlatdar.

Tatya had opened a camp in Dhanakwadi during the dreadful drought of 1877. Here, a thousand bhakris were distributed daily and free of cost to the blind, the lame and children. My mother and other women had been appointed there for cooking. The camp was being managed by Savitribai. Tatyasaheb, Ramshet Udavane and Dr. Shivappa took care of the expenses for this initiative. I would sometimes accompany my mother to this camp.

In 1878, Tatyasaheb bought farmland downstream the Mula-Mutha dam and started a large plantation which he continued to cultivate for the next seven to eight years. He owned about 15-20 oxen, one or two cows and a horse, which would all be kept on the plantation. My father was employed as an overseer by Tatyasaheb to run this plantation; my father would be employed for one job or the other by Tatyasaheb. Tatya had taken canal water for the plantation from the pipeline numbered 17 ½, which is still known as ‘Phulyanchi Nali’ [literally, Phule’s irrigation channel]. Tatya had planted a variety of local and foreign vegetables, fruits and flowers, intentionally, and would utilise both domestic and imported fertilisers. The plantation area covered about 50 acres. He set up a sugar cane mill and sold thousands of rupees worth of jaggery, vegetables and fruits. He also started a business enterprise to supply vegetables to Mumbai. Upon the completion of the Yerwada bridge construction, he invited labourers from the construction site as well as the plantation to the farm and hosted a grand feast for them.

Tatya would treat all the workers employed by him with affection, and there were quite a few under his employment, including workers employed for construction contracts, plantation, metal cast shop and domestic work at home. He earned a lot of money, but spent just as much indeed.

In 1888, Rao Bahadur Hariraoji Chiplunkar threw a grand feast in the honour of Queen Victoria’s son, the Duke of Connaught. Tatya arrived at this feast dressed in a calf-length dhoti, torn turban, coarse blanket (ghoṅgaḍī) on the shoulder, sickle tied to the waist, torn footwear and a stick in hand. He rose to give a speech in this attire, thanked the Duke of Connaught and said, “The attire that you see me in, that’s the condition of the 20 crore farmers in this country. We demand compulsory education. When you return to your homeland, convey this message to your mother on behalf of the farmers of this country.” Tatya spoke passionately on the occasion. I witnessed him wear the torn farmer’s attire while going to the feast and upon his return, he narrated his speech at home, and I also heard about it from others.

Tatya’s lectures used to be held at the military contingent stationed in Pune. I had gone to attend his lectures twice at the Ghorpadi Cantonment. Military officials like Major Daryajirao Thorat would invite him to deliver these lectures.

I had grown up hearing of the fierce family feuds amongst Tatya’s father Govindrao and his uncles Ranoji and Krishnaji. Krishnarao and Govindrao had been fighting together against their brother Ranoji, because Ranoji had purloined the land given to the family as a grant by the Peshwa. The disputes passed over to the next generation as well, which I witnessed. Ranoji’s descendants — Tatya’s cousin and nephew — harboured enmity towards him. Ranoji’s son Baba Phule, and nephews Mahadba Phule and Sadaba Phule did a lot of manoeuvring, with the fear that Tatya would pass on his estate to Yashvant instead of them, and tried to convince Tatya to adopt one of them, but Tatya resolutely refused to listen to them. This led to them exiting the Satyashodhodhak Samaj and joining hands with the Brahmin party for sheer personal gain. Enraged by this, towards the end of his life Tatya instructed everyone that his nephews who had joined the Brahmin party should not be allowed to touch his dead body after his demise. Tatyasaheb died on the night of 27th November 1890 at 2.20 am. The same night, Mahadba Phule insisted it was them, his relatives, who would carry the body away. But Dr. Ghole[1]Vishram Ramji Ghole and Lokhande[2]Narayan Meghaji Lokhande called the police, and Mahadba Phule was removed from the scene. Tatya’s body was then cremated on the afternoon of the 28th at the crematorium near Lakdi Pul (bridge) where many people spoke about Tatya’s life at the condolence meeting. The speakers included Dr. Ghole, Narayanrao Lokhande, Bhau Kondaji Patil and others. On the third day, his ashes were brought home in a celebratory wake, with games of dandpatta being a part of the procession, and were buried in the tomb he had assigned for himself by the well in his house.

Tatya was a person of Truth. He couldn’t tolerate lies. He always spoke with candour and honesty with everyone. His name, therefore, commanded respect and awe. Everyone who called upon his house was treated with warmth and honour, and guests coming over for lunch or dinner were an everyday occurrence. Sometimes, these guests were influential people from abroad.

Pune’s City Magistrate Mr. Plankitt, a good friend of Tatya’s, would call on him every now and then. He was a kind soul and a gentleman, and was quite well-liked in Pune at that time. European officials from the Irrigation and Education Department would sometimes visit Tatya, and he would visit them often too.

The Governor hosted a feast at the levee by his bungalow once a year and he also organised darbars at the Council Hall now and then. On these occasions, men riding horses were sent to deliver the invitation to Tatya. I too had accompanied Tatya to the levee twice or thrice. However, for uninvited people like me, there used to be separate arrangements.

Tatya was a member of the (Poona) Municipality for about 10 years. Roads were built through his efforts in the Old Ganj Peth locality, which was a decrepit hamlet before.

Now I want to share important details about Savitribai: she was a virtuous woman and her heart was filled to the brim with compassion. She was immensely kind towards the poor and would always donate food. She was generous — providing food for all, and upon seeing the tattered garments of impoverished women, she would offer them her own clothing. This proved to be a considerable expense for Tatya. When Tatya remarked, “Such expenditures are unwise,” she would offer a serene smile and reply, “What can we carry with us beyond this life?” At this, Tatya would fall into quiet contemplation. They loved each other a lot. Savitribai was deeply concerned about the progress of women. On her insistence, Moro Vitthal Walvekar had started the magazine Gruhini (home-maker). She offered wise counsel to women. She was good looking and of medium build. She had a perpetually peaceful countenance. How much can I praise her? She was like a goddess in Tatya’s house. After her bath every morning, she would mark her forehead with vermillion. She was a sadhvi (a saintly woman) who served her husband and accompanied him in his sorrows. When Tatya was struck with paralysis, she took great care of him. I will not write about it here due to lack of space. She would always call Tatya as ‘shethji’ and Tatya would address her respectfully with ‘aho, kaho’.

When Tatya realised that his death had neared, he expressed the desire to see his friends from Mumbai. He was able to meet them all a day before his passing. At that moment, he gave important instructions to the people who had gathered to see him such as Dr. Ghole, Pandit Dhondiram Kumbhar, Bhau Kondaji Patil, Narayanrao Lokhande, Ramayya Venkayya Ayyavaru and Moro Vitthal Walvekar. The counsel was on the lines of: “Behave truthfully, don’t stray from the Truth, God will help you, continue the work of Satyashodhak Samaj. My spirit will help you even after my death.” You have written about this entire counsel in your biography published in 1927, and all of that is indeed correct.

Tatya’s exact birthdate is not known. His stepmother Chimnabai died around 1883. Chimnabai, and occasionally Tatya as well, would reminisce: Shaniwar Wada was set ablaze on a night in the month of Phalgun in 1827, and by dawn the following day, Tatya was born. I remember the date of his passing well. I had written it down; the newspapers had published his obituaries. He was not that tired but fate took him away early. There is very little humans can do about it. So be it.

I am writing and relaying this information to you today with the permission of my mother Thakubai. My mother is still alive and is currently over 90. Her health and memory are in good shape, and she still helps with some small chores in the house. I have sent the information as remembered by my mother and me. If we remember more, I will write and send it across.

(Mahadu Sahadu Waghole’s memory has been translated by Tejas Harad, edited by Rucha Satoor and Ninad Pawar, and peer-reviewed by Suraj Thube.)